AMA Ethics Talk (regret, detrans & trans health)

Kinnon joined "Ethics Talk" on the AMA Ethics Podcast to discuss transition/detransition/regret. What do we know about it? And, just as importantly, what more do we need to know.

This is a summary of a podcast interview with the American Medical Association’s Journal of Ethics podcast, with host Tim Hoff. It was part of the issue on Regret in the Moral Psychology of Surgical Professionalism.

This interview was pretty quick at under 30 minutes and I was glad to be invited to participate. It covered some of the 101s of trans medicine, detransition-related medical/surgical care, and researching detransition and regret.

Although this is an issue that has become extremely politicized and the subject of relentless “culture wars,” there are indeed emerging questions and with regards to research and care. Here’s my view as both an academic researcher and a trans person (trans masculine) who transitioned in ~2010—the beginning of what we might think of as being the “transmasc takeover” (aka the sex ratio flip to favour assigned females/trans masculine youth and young adults in gender clinics and trans community samples): an approach to address the growing public skepticism toward trans medicine and the broader erosion of trust in public health is to be honest about what we don’t know, to be more critically minded as a field (including self-critical), and to update and improve the overall quality of our research. That, of course, is becoming much more difficult when public health and LGBTQ+ research has been brutally decimated.

Here are a few highlights covered in the Ethics Talk interview

Known estimates of detransitioning following hormonal treatments are 1-10%, and lower for post-surgery, but existing literature has some important limitations.

Historically, the study of “regret” in trans medicine was applied to cover wildly discrete concepts such as change in identity/gender presentation, decisional regret without detransitioning, legal gender marker reversal, etc. The concept of regret, historically, did not refer to dissatisfaction with interventions or minor complaints with surgical technique or outcomes.

One of the most frequently cited studies on the prevalence of “regret” (Dhejne et al., 2014) operationalized regret by looking at a subsample of applications made to the Swedish government to legally reverse the gender marker following surgical gender transition. This study did not collect or analyze data on patient satisfaction with treatments or examine identity outcomes following gender transition among the full population of trans people included in the study.

Acknowledgement that the older, binary, treatment-cascade approach can potentially pressure trans and nonbinary people into pursuing interventions they might not need, want, or benefit from, risking later regret. This came up in my last study, with participants reporting that they were required to go on testosterone to access top surgery. These participants later regretted the effects of testosterone but not the surgery. This type of practice is no longer recommended by the standards of care.

Treatment regret expressed by a minority should not be a reason to restrict or ban medical care for all, but that there is a need for better long-term outcomes research to understand key unknowns.

The increasing challenges in conducting research in this field due to political climate, polarization, debates about care (this interview was recorded in December 2024, and a lot has already changed since then).

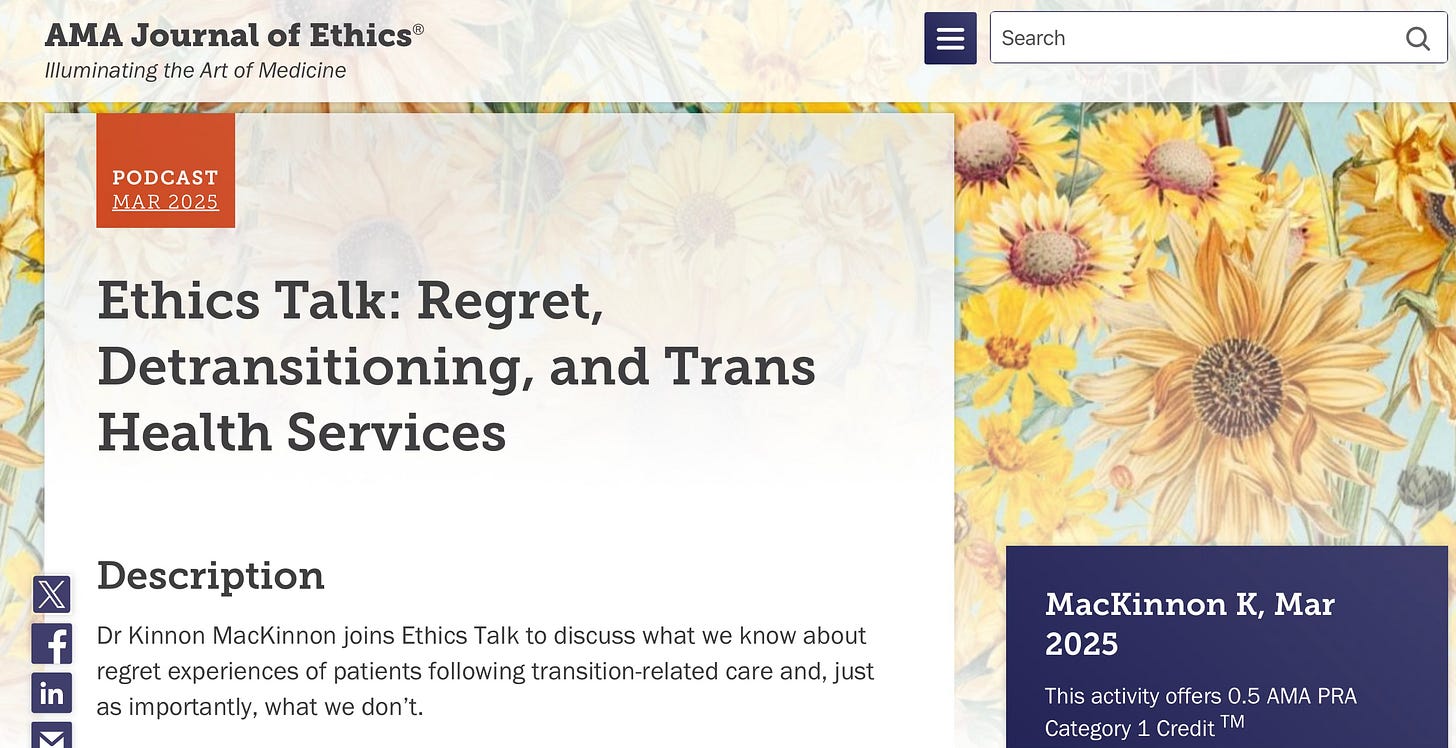

On the comparison of transition regret with orthopedic surgery regret

One of the more important issues that I spoke to in the interview is why I dislike comparing the prevalence of transition regret to regret rates in orthopedic surgery to win culture war debates (e.g., “Well, 20% of people regret knee surgery”). I’m sure you know the bit.

I suppose it’s useful to have comparisons and points of reference, and I admit I know ten-fold more about transgender medicine than orthopedic surgery, but still I find the two incomparable. Mainly, for the following reasons:

orthopedic surgery regret has zero bearing on civil rights for orthopedic surgery patients, whereas trans medical sciences has been baked into the trans civil rights project since the beginning;

the study of orthopedic surgery regret and transition-related surgery apply different definitions of regret and different methodologies. In orthopedic surgery studies, studying dissatisfaction with procedural techniques or with the overall decision to pursue surgery is common. In many studies of transition-related surgery regret, regret is operationalized as seeking or desiring a reversal surgery (it would be like if knee replacement surgery patients went back to their surgeon to ask for their old knee back…). It’s like comparing apples and oranges and such;

the trans population tends to be a more vulnerable patient group who carry a high burden of mental health challenges, disability, somatization, neurodivergence, and living with the stigma and minority stressors of being trans/nonbinary. These factors can make surgical recovery more socially and psychologically complex. Age is another component of vulnerability with regards to youth. In The Netherlands, the age to access mastectomy/chest masculinization was lowered from 18 to 16 in 2020, emphasizing that, with the lowering of age restrictions, it would be important to monitor this group’s “postoperative satisfaction, possible regret and quality of life” (van der Sluis et al., 2024);

the cultural messaging around trans surgery in media and social media for the last 10+ years, in my view, makes it difficult to compare with knee surgery regret rates. Patients think about and relate to these surgeries in completely different ways.

The discourse of minimizing the significance of detransition/regret is something that I have admittedly become more sensitive to over the years, after interviewing (and collecting data from) so many people who feel lost in the politics, and neglected by my fields of research. After I began researching this topic a few years ago, and subsequently appeared in a couple of news articles on the subject, I began receiving e-mails from people looking for support and resources. Sometimes these were parents who had supported their trans youth to transition, and now as young adults they were detransitioning and struggling. Sometimes I heard from detransitioners who were searching for someone to connect with who might listen. Some had lost important connections to trans friends and LGBTQ+ community for expressing regret. Others who contacted me were gender-affirming clinicians. Over the years, many e-mails landed in my inbox but I had few resources on offer other than, sometimes, I might offer to chat on Zoom. I was at a loss for how to respond, fearful of what the personal and community costs might be in continuing to research detrans people’s experiences. Perhaps the most challenging aspect was acknowledging it was even happening.

Still, I felt it was my ethical and civic duty to carry-on, and that the field of trans medicine/LGBTQ+ health would need to begin the difficult work of discussing and developing formal care regarding detransition.

Although said with good intentions of supporting trans people and preserving access to care, to quip that “more people regret knee surgery” can result in minimization, alienation, and people feeling swept under the rug. At precisely the time when they might need support the most.

The vast majority of trans people do not regret surgery. Most trans people feel affirmed and helped, not harmed, by medical transition. But trans medicine has risks, side effects, and complications. Sometimes these are relatively minor and resolve with time, other issues can become chronic conditions, while others can be treated with additional medicines, surgery, or physical therapy. But there is a risk that surgeries (more often with genital surgery) can have serious complications, even being disabling in rare cases. While that can apply even for trans people who never express any regret, surgical complications can prompt detransition and regret. Some might argue that detransition+regret following surgery is in itself a serious complication (I am not necessarily endorsing this, especially not categorically, but there are indeed individuals who would put their experiences in those terms).

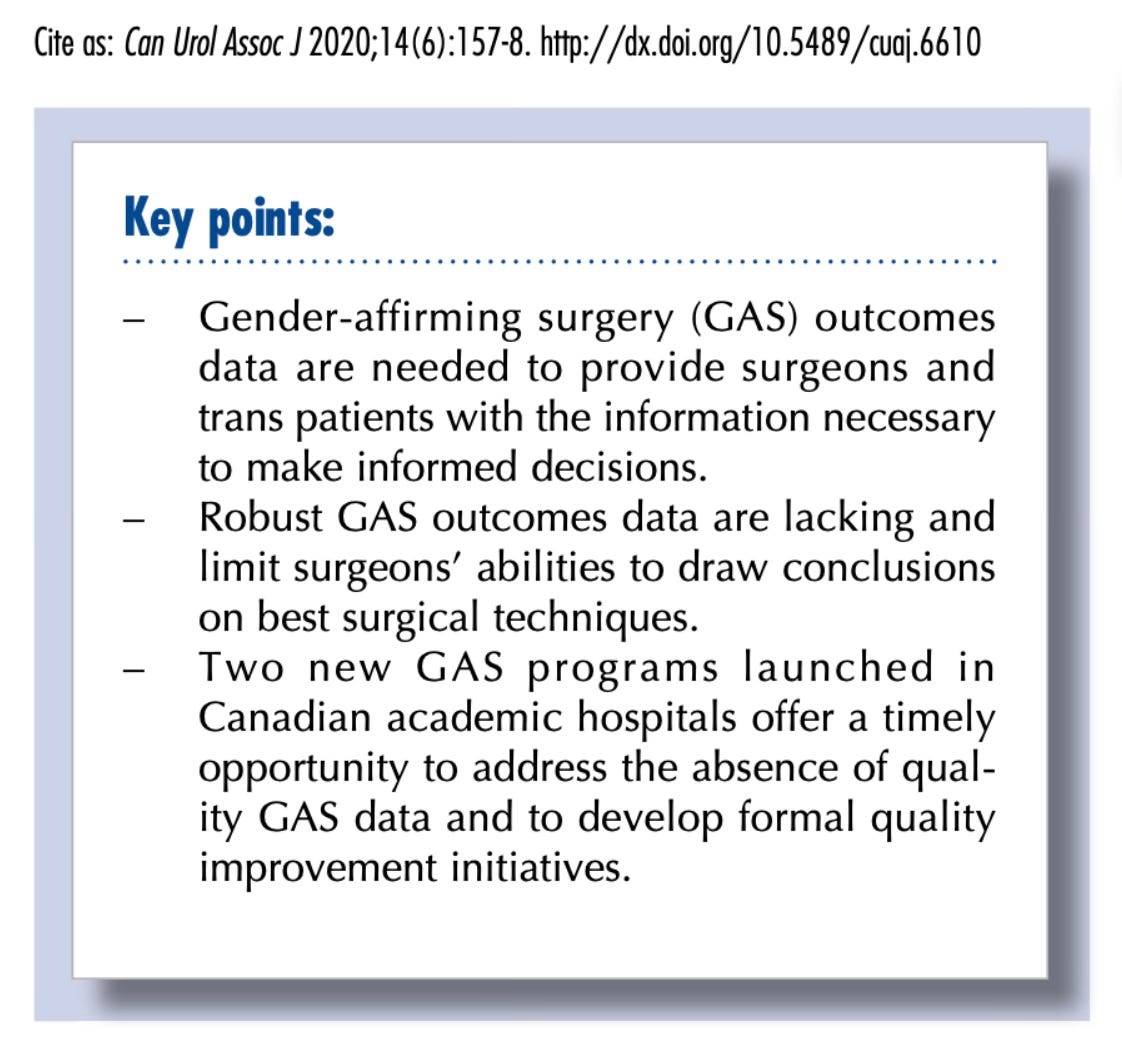

In my view, the current state of the research is a direct reflection of the long-standing minoritization of trans medicine as a specialty. In Canada, until recently trans surgeries were only available in a couple private clinics, not in academic research hospitals where the vast majority of research is conducted. Trans medicine has a history coloured by scientific advancements, and also includes rogue physicians experimenting with dangerous hormone dosing, and back alley surgeons. This is partially due to trans people being a small, vulnerable, and sometimes desperate patient population existing largely in the margins of society.

To this day, to access surgery, many patients travel far distances, sometimes even leaving their home country. They remain at the surgical site for a short recovery period before heading home. And unless procedures are staged (like metoidioplasty or phalloplasty), patients rarely return to be seen again. As a result, collecting short, medium, and longer-term surgical outcomes is infrequent, which has consequences on research and decision-making. Prioritizing better surgical research and more transparent outcomes is a top priority of trans and nonbinary experts, and is something I have written about along with two Canadian gender-affirming surgeons, Drs. Ethan Grober and Yonah Krakowsky.

With greater public health investment, the state of the science in academic trans medicine could be improved, and might therefore become less vulnerable to being politically weaponized for its flaws.

The full recording of the podcast is available here. Feel free to share any thoughts or questions in the comments section.

Thank you for reading The One Percent!

If you enjoyed this post, please share it with your friends, family, or colleagues:

You can also subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work:

Kinnon, I am glad there is somebody like you, from your background, trying to research detransition in good faith. But as I have read The One Percent in good faith, I can’t escape the feeling that your own trans identity, and adherence to or faith in the subculture forces you to frame detransition as being part of the “overall trans experience”, rather than a aberrant or disconfirming phenomenon which could, and in many cases does, fly in the face of trans as an ideological framework. This notion that “trans is rare” is only something that could be said by someone with no children of adolescent age right now. Because you might not be able to admit there is a socially mitigated surge in this narrow age group, you risk to undermine the good will you might otherwise garner from not being perceived as taking an ideological stance.

No one is born in the wrong body. Dress as how you like, be non conforming but don’t tell me you are the opposite sex you are which I can see with my own eyes - keep this belief system out of schools- https://open.substack.com/pub/pitt/p/my-colleagues-have-failed-you?r=505il&utm_medium=ios