Moving (De)Trans History Forward

"An open community conversation on detrans issues must coincide with the discussion of trans issues"

This is a guest post written by Maddie, a research assistant for the DARE study and The One Percent. Maddie has previously written about the possibility of building bridges between trans and detrans communities and discourses. You can read a previous post by Maddie here.

I always expect talking about detransition to feel like being on Twitter/X. Talking about detransition on Twitter/X is not something I find fruitful.

To share a little about myself, I am a person with experience of detransitioning. I am also someone who sees the value of research and a growing knowledge base. Because of this, I want to talk about and research detransition without tension, as part of an effort to understand the experience fully, with nuance, and as a part of a larger social phenomenon. When I get the opportunity to do this, I always find it healing. I have been a part of the DARE research team as a research assistant for about a year, so far.

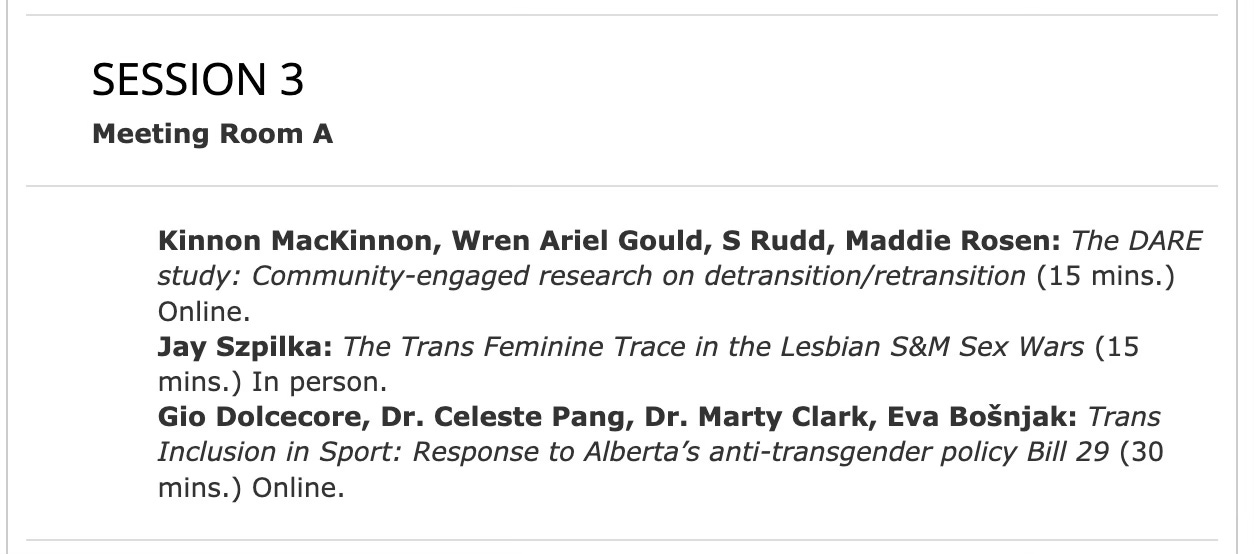

On March 28, I had the opportunity to be on a panel for the DARE study at the Moving Trans History Forward conference. Joined by a few other research teammates, Wren Gould, S. Rudd, and Kinnon MacKinnon, we presented some preliminary findings from the study—demographics, a touch of analysis, and focusing on the steps taken to be inclusive and LGBTQ+ community-engaged. Presenting about detransition-related research or experiences is strange for me in that any stage fright I may have is almost entirely superseded by my anxiety about how people will respond. As I said: I worry it will be the same snippy, skeptical, polarized discourse as social media discussions about the subject.

I have learned that, even in the context of academia, people who are scientific and open-minded can still be hesitant to talk about detransition. I don’t blame them. I imagine that it scares them; not just the idea that things are more complicated than long assumed, but the way that complexity can (and has been) weaponized in in a trans-hostile political climate. That’s why, at the conference—which I attended remotely—I was pleased to hear the moderator open our session with a request for attendees to remain open minded and ask questions. I’m not sure whether every session started that way or if it was said in anticipation of reactions to the topic of detransition specifically, but it allowed me to let out the breath I’d been holding, thinking about presenting on detransition to an audience of mostly trans and nonbinary people (or so I assumed).

Understanding detrans research requires empathy; it asks people to understand worldviews and perspectives that sometimes contradict what progressive and trans rights discourse assumes is empirically true and moral. By now, the topic of detransition has become fairly right-wing coded, even if most detransitioners themselves do not hold these political values. It is a difficult task for those who have felt the impact of anti-trans rhetoric, including that which cites detransition as its basis, to listen non-judgementally.

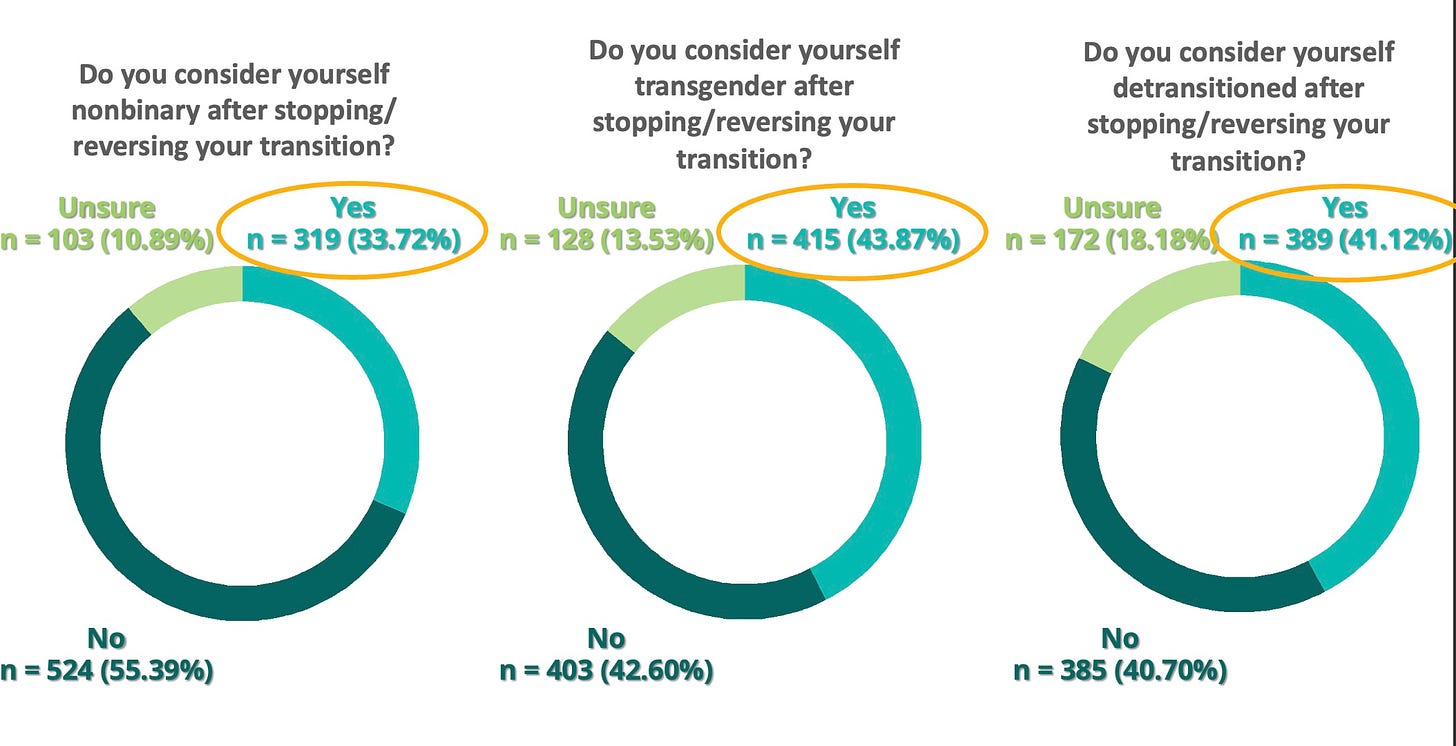

Our presentation was followed by two others: one examining historical trans influence in lesbian/bisexual discourse, and another on Alberta’s proposed laws around trans youth participation in sports. When I first detransitioned, the idea of detransition being discussed with empathy and complexity in the same metaphorical breath as “regular” trans subjects felt like an impossibility. The people who wanted to hear about one were not open to hearing about the other, and vice versa. Trans spaces wanted entirely trans-affirming narratives. Gender-critical spaces wanted entirely anti-trans narratives. So, it was a welcome change to participate in something that understands the experiences of transition and detransition as cousins. As our presentation explained, detrans, trans, and gender diverse demographics can be deeply intertwined, so it really makes no sense for them to be moved outside the established sphere of trans studies.

The Q&A session was sadly brief due to time constraints. The only question directed at our team was the expected one when it comes to detrans research. It went something to the effect of, “how do you make sure your research isn’t wielded against trans people?” However understandable this concern might be, I find it a bit underwhelming that this is so often the question people have about detransition. The principal investigator of the DARE Study, Kinnon MacKinnon, responded in validating the concern, but he also said that, truthfully, it’s not always possible to predict how political actors will use research, no matter what the research team says or does.

One of my colleague also tackled the question of weaponization—a bit more boldly, even—by pointing out that research showing positive outcomes with gender-affirming care is also weaponized due to using “low-quality” research designs, and we continue to conduct it anyway. I really appreciated this response, because I am tired of detrans people being treated as uniquely “risky,” and therefore acceptable to ignore or censor. Is that how science ought to work? This anxiety about misuse always serves as an unwelcome reminder of how the current needs of detrans people are expected to take a backseat to the preservation of gender-affirming care. My colleague’s response underscored that disparity, and to hear it in an academic-community venue was a powerful moment for me.

Although I wish there had been more time for questions and discussion, I hope our presentation left attendees with a fuller perspective of the experiences and diversity of detransitioned/retransitioned people in the US and Canada. If nothing else, I hope our presence there stuck with them. The name of the conference—Moving Trans History Forward—is significant in combination with our presentation. To me, seeing detrans research acknowledged as a part of the story of trans and gender diverse people feels like a big step in moving detrans history forward as well. It’s clear to me that an open community conversation on detrans issues must coincide with the discussion of trans issues. We can’t do that in reactionary, algorithm-driven social media settings. In an academic research context, however? As I saw at this conference, we absolutely can.

Thank you for reading The One Percent!

If you enjoyed this post, please share it with your friends, family, or colleagues:

You can also subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work:

I am in total agreement that understanding detrans research requires empathy, lots and lots of empathy. IF someone in transition is presumed to be vulnerable, imagine the mindset and state of vulnerability of someone who "dares" to detran. My question is expanded on below, but how is regret different from detrans, and I mean real regret. Detrans research seems to be missing out on the sub-population with no voice?

The question of weaponization is a dishonest framing. This is the Dr. Johanna Olson-Kennedy, nine-year, $10 million error. You can't shield people from the result of your research IF you don't like the result. This is something trans related research seems to suffer from and such dishonesty will send transition back into the dark days. The ethical job of the researcher is not to cultivate a desired result. It is to speak honestly and find answers to substantive and meaningful questions. I appreciate a post-modernist will spin out of control if I say "find truth". It is about having a better understanding of a problem - hence if the result doesn't prove the hypothesis an ethical researcher ponders and explains why, one should never run from a result or fear weaponization.

SO WHAT: Where does this leave us with detrans research? Is it finding truth? Sometimes it feels like we are trying to create as many sub-populations as possible to obscure the obvious? People detransition, some never get to detransition because the regret is so severe.. As a matter of trauma survival it seems so many will try to find a positive to transition. Its how they survive and truly cope. In some respects like Stockholm Syndrome we find a way to survive. Ultimately, it becomes difficult to honestly parse out the "why" people detrans. It almost feels irrelevant in the bigger picture. It is all the more corrupt when we are describing individuals that socially transitioned at a young age given they had no way to comprehend what they were doing and where it would lead.

MY QUESTION: Why not capture those who can no longer speak? Case in point, two adolescents committed suicide during the *Chen et al (2023). Is it simply an acceptable number "lost to follow up"? Chen (2023) certainly appears to treat it that way. So how are the dead accounted for? Given two individuals never got to the point of detrans, are they excluded from the one-percent? We seem to be missing a growing segment of the population that have suffered a transition outcome far greater than detrans, I looked at a review of the UKs Tavistock GIDS initiated, intended as a follow up study to the famous "Dutch protocol research". Their puberty blocker study initiated in 2010 during a somewhat less turbulent time. By the time the study began in 2011 it had enrolled 44 children aged between 12 and 15 and the study ran over a three year period. The study was reluctantly released nine years after it started and findings confirmed blockers were not "a pause" but part of a pathway given 43 out of 44 participants moved on to cross-sex hormones. There is nothing to fear in this finding; however, the study went unpublished for years. When it was revealed we learned a more disturbing pre-post outcome. After a year on blockers, ‘a significant increase was found in the first item on the Youth Self Report questionnaire: “I deliberately try to hurt or kill self”. This was cross reference with parental feedback. While this raises ethical questions ultimately it seems there are now 43 people that would make an ideal longitudinal study group to capture detrans rates and potentially an even worse outcome.

* Chen, D., Berona, J., Chan, Y.-M., Ehrensaft, D., Garofalo, R., Hidalgo, M. A., Rosenthal, S. M., Tishelman, A. C., & Olson-Kennedy, J. (2023). Psychosocial functioning in transgender youth after 2 years of hormones. New England Journal of Medicine, 388(3), 240–250.

https:// doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa220629