The hidden cost of overzealous activism in the media

Activism for the rights, medical treatment, and well being of trans and gender diverse youth must continue—just with a little more nuance and respect for research and the scientific process.

This is a guest post written by one of our research assistants who lived as a trans boy for her youth before detransitioning to a female identity in her early 20s.

(Note: On The One Percent, we aim to showcase a wide range of LGBTQ+ identities and experiences and to communicate experiences of detransition. From our respective research including face-to-face interviews with detrans folks (about 130+ people), we have learned that feeling unrepresented or misrepresented within mainstream discourses about trans issues and gender-affirming care is a commonly held feeling. Many detransitioners accessed treatments many years ago when the idea of detransition was never discussed, thinking it’s too rare to ever happen to them personally.)

In the fall of 2022, I attended a research symposium at York University, organized by Canadian researchers Kinnon MacKinnon and Annie Pullen Sanfaçon. This event was a first in the world of transgender research, a symposium specifically focused on detransition (that is, when a person transitions and later experiences a shift in their identity). Despite this topic’s reputation as the domain of transphobic alt-right agitators, this symposium was very trans-friendly, organized by a trans person and presenting papers written by majority LGBTQ teams. Given how polarizing the topic has historically been, this trans-inclusive event should have been a breath of fresh air—a sign that researchers were genuinely interested in a non-political understanding of all outcomes of gender transition, not just the success stories.

It wasn’t quite that; it was rather tense.

Seated at my table were myself, a few clinicians, a researcher, another detransitioned woman, a trans person, and a journalist with the CBC (Canada’s NPR). The journalist stuck out to me that day. He hardly said a word after introducing himself, aside from announcing to the table: “I can’t write about this”. That admission hadn’t surprised me; transgender rights being a political world I am familiar with, I was well aware how taboo the subject was. I could see how reserved so many attendees stayed. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t also nervous to be at this symposium. Looking back on it, though, I find my acceptance of this fact a bit shocking. What sort of social conditions have led to a point where major publications are reluctant—afraid, even—to report on research?

To report on such relevant research, at that.

Some of this reluctance is a result of right wing attacks on transgender people, to be sure. It’s understandably challenging to balance truthful reporting with the knowledge that some people will abuse any hint of uncertainty to argue that the whole endeavor of supporting gender diverse people is a failure. Still, I think there’s more to the story. I think it should concern us that even potentially negative outcomes of gender medicine have become almost unspeakable, considering the level of certainty that activists and medical associations have endorsed in the last decade.

How can patients make informed decisions if some information is suppressed? I say they can’t.

Frustratingly, others seem to disagree. I do believe that they and I have a shared goal—for gender diverse youth to receive the best possible, evidence-based medical care—but I must admit that I think we as a society have skewed too far on the side of activism on this one, and are leaving research behind in the process. Gender-diverse youth are paying the price—in particular, those of us who ultimately end up detransitioning.

GLAAD v. the New York Times

Three months after I attended the symposium on detransition, tensions boiled over between trans activists and the media. Questioning the status quo of youth gender care was no longer confined to fringe reactionary media; now reputable, less sensationalized outlets had begun to report on the growing debate too. Debate over trans youth had, for several years prior, been conceptualized by mainstream media as a fight between progressives and conservatives, an issue rooted in ideology rather than medicine. Now they were talking about medical questions—not whether providing medication and surgery to trans youth was moral, as conservatives did, but whether it was effective, and whether there was enough evidence to justify current guidelines in light of dramatically shifting patient demographics.

I myself was among those in the shifting demographics as a youth, assigned female at birth, later diagnosed autistic, and without any real signs of gender nonconformity since childhood. I only began seeing myself as a trans man at the age of 15 after being involved in Tumblr.

Activists, I think understandably, saw this as a threat. It can be hard to distinguish genuine critique from hateful rhetoric in such a charged political climate, to know who is truly concerned for the well being of trans and gender nonconforming children and who is simply uncomfortable with the idea of trans children. This is how the New York Times—one of the first centre left outlets willing to cover these debates seriously—found themselves the subject of activist ire.

LGBTQ+ activist group GLAAD protested the New York Times directly, both with a billboard truck parked outside their offices and with an open letter calling for change. The list of signatories on this letter is rather long and well-reputed, including activist groups, like PFLAG and The Human Rights Campaign; celebrities, like Lena Dunham and Margaret Cho; and even the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) itself. This was not a small undertaking on GLAAD’s part, and looking at the list it feels quite authoritative.

Among the letter’s demands is the following:

“STOP: Stop printing biased anti-trans stories. Stop the anti-trans narratives immediately. Stop platforming anti-trans activists. Stop presenting anti-trans extremists as average Americans without an agenda. Stop questioning trans people’s right to exist and access medical care. Stop questioning best practice medical care. Stop questioning science that is SETTLED. We will do all we can to make sure that Times writers and editors have the necessary information and access to experts to report responsibly on trans people and issues. But we will be strongly recommending that trans youth and their families skip interviews with the Times, in order to keep them out of harm’s way. Timing: Immediately.”

“Science that is SETTLED” is a bit of an oxymoron, in my opinion—can science ever be truly settled? I don’t know of any field where inquiry has stopped because the field is finished, nevermind something as rapidly evolving as care for trans youth.

As it turned out, the NYT was right: the debate within medical organizations and clinicians was only intensifying. With this, activism, journalism, and research grew more polarized.

Unsettling science

Despite GLAAD’s claims, it’s become clear that something has dramatically changed in the world of gender medicine. It’s easy to believe that this sudden re-questioning of things stemmed exclusively from very real right wing attacks on trans healthcare—especially moves in several US states to ban this treatment for minors all together—but the reality is a bit more complicated than that. This shift was happening in a somewhat less inflammatory context in other countries too.

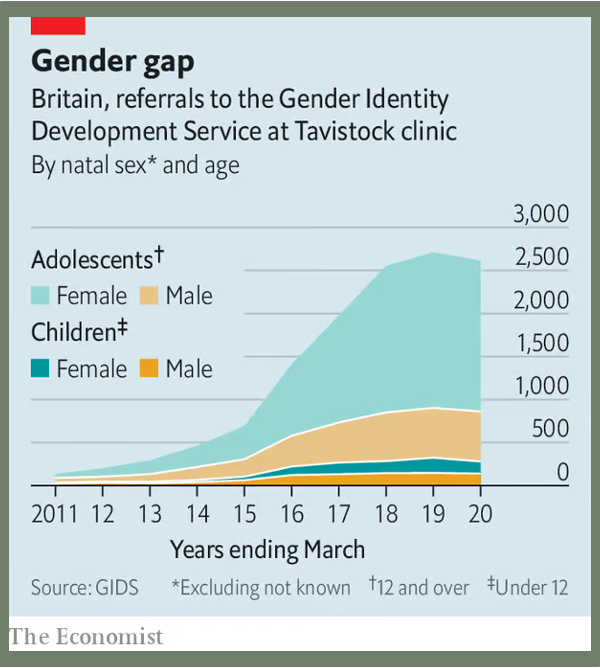

For decades, the Tavistock trust’s Gender Identity Development Services (GIDS) was the only clinic in the UK that provided gender related care to youth. For most of its history, GIDS had seen fewer than 100 referrals per year, three quarters of them male. In 2011, the sex ratio evened out. By 2016, referrals had increased by nearly 15 times, and the sex ratio had nearly flipped: now two thirds of referrals were female. Not only that, but the nature of the cases had changed, now with many patients experiencing complicated concerns with an unknown relevance to their dysphoria. GIDS was struggling to keep up with the ever-increasing size and complexity of their workload.

More than that, there were growing debates over how the existing evidence applied to this new cohort of patients. Even within the Tavistock, in a purely medical and psychosocial context, clinician concerns about this were dismissed as transphobia.

In response to this, NHS England commissioned a review led by Dr. Hilary Cass, a pediatrician and former president of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. This report was to look at not only the state of GIDS care provision, but also at the evidence for pediatric gender-related treatments as a whole.

Many claim that this increase can be explained entirely through increased societal acceptance and awareness, allowing young people to realize themselves in a way they simply didn’t have access to previously. Some have even suggested that it might be immoral to ask why this might be happening—for instance, a transgender charity worker who told the Guardian,

“Research into the cause of a marginalised identity can make you feel nervous. It makes me wonder: why would you want to ask that question?”

This would be an understandable position if we were talking purely about identity… but we aren’t. We’re talking about giving life-altering, irreversible treatments to a population of children and adolescents who have significantly elevated rates of autism, mental illness, and adverse childhood experiences. What also seems notable, is that the rise in transgender identities seems to be driven largely by young, white, assigned females or transmasculine people, or at least that seems to be the emerging picture in the United States.

Surely that warrants some investigation into how these experiences and identities may interact, especially given a growing understanding that an unknown number of people do end up discovering their gender dysphoria stemmed from trauma, mental health issues, or internalized homophobia. When we are calling a treatment “life saving care”, there is plenty of reason to ask why the need for said treatment has boomed.

This is especially pertinent given the high-pressure rhetoric with which parents are sometimes presented with these choices; as far back as 2011, youth gender clinicians were quoted as saying:

“We often ask parents, Would you rather have a dead son than a live daughter? … These kids have a suicide rate that is astronomical compared to any other group.”

It can’t be purely about identity if we’re talking about it like this. It deserves to be treated like medicine and public health sciences—and that means being open to research when things change as they have in the last decade.

In response to the Final Report of the Cass Review, which found there were a concerning number of unknowns, activists immediately moved to dismiss the entire review as biased and “anti-trans”. To be fair, all research involves some degree of bias, but misunderstanding spread quickly, to the point that the Cass Review’s website needed to add an FAQ addressing common misconceptions about the review’s process, and about normal review procedure. Despite the backlash, the NHS has adjusted their guidelines, restricting the use of puberty blockers to a clinical trial context. Norway, Sweden, and Finland have also adopted a more cautious approach in recent years. On the other hand, France has recently produced updated guidelines for pediatric gender-affirming healthcare that are affirming of these treatments’ benefits (and their unknowns, stressing that pubertal suppression to hormonal treatments does not have “favourable” data regarding fertility). The European Academy of Pediatrics’ guideline on managing gender dysphoria in children and adolescents suggests some caution around medical treatments in trans young people under the age of 16, particularly with regards to fertility preservation.

Would there be the same strong feelings about a review looking into, say, the efficacy of a cancer treatment? Would they be so cavalier about the long-term outcomes of a new drug for diabetes? Generally speaking, I think not—those are things that do need treatment, but haven’t been turned into a political football the way care for transgender people has. Despite the understandable defensiveness on the part of activists, this lumping of anything remotely critical into the “transphobic” bin may be preventing trans youth from getting the care they need. It’s tricky now that identity and medicine have become so intertwined.

Unfortunately, there is another problem that happens when too much dogma gets in the way of research: once there are enough naysayers, people start to look into things more closely despite the pressure not to.

If it turns out the advocates were wrong—or worse, knowingly wrong—then it begs the question: why the enormous emphasis on certainty? It’s a bad look; How can someone who wants to support trans youth know what to trust if the experts are openly untrustworthy?

Looking forward

Where do we go from here? How do we fix this? I’m no expert, but I think the first step is to rebuild trust. Activists—on all sides—need to be honest, to allow researchers the intellectual freedom they need to do their jobs well, and to extend understanding to those who are supportive-but-concerned, or who have questions. No matter how strong the urge—and no matter how valid that urge is, given the genuine threat of transphobic legislation—I can’t see this defensiveness working out in the long term. It’s already starting to crumble.

There ought to be a way to discuss medicine separate from identity, and to open the floor to rigorous research and discussion—the same as any other serious medical treatment. We are now in a position where countries like the United States have not only shattered trust with the public on this issue, but have also assessed the state of the evidence to be wildly different from countries like the UK, Sweden, Finland, and Norway.

For a prior post that applies the philosophy of science to examine how “both sides” interpret evidence based on different values, see:

Why can’t we agree on the science of gender-affirming healthcare?

Psychology and psychiatry—the “psy” disciplines—have long carried the stigma of not being “real sciences,” partly because they come from philosophy rather than the natural sciences, and partly because they deal with less tangible phenomena—thoughts, emotions, behaviors.

Trans youth need as many allies as they can get, and I believe the path to that lies in honesty. Activism for the rights, medical treatment, and well being of trans and gender diverse youth should continue—just with a little more nuance and respect for the scientific process.

This is the first thing that The One Percent has posted that's got me a bit frustrated. If we are talking about transition-related healthcare in terms of "effective treatment" it begs the question of what exactly we expect hormones and surgeries to do for a person psychologically, and what constitutes "damage" in that arena.

The vast majority of the trans people I know do not think of gender-related healthcare in these terms, but rather in terms of bodily autonomy, where a gender-related diagnosis is a necessary evil to be able to exert desired control over the shape of one's body. It's not comparable to cancer treatments because it's not a "treatment" for anyone but a tiny number of people whose distress is extreme-- trans people have leaned on "I need this or I'll die" rhetoric even where it isn't accurate to every individual because there are so many hurdles between simply allowing us to do with our bodies as we please.

The primary lack of trust is between patients and clinicians because of a history where "because I just want to" is not seen as a good enough reason to transition, and between children and parents who believe they are incompetent to make this specific decision-- as if any other decision made by or on behalf of a child is not equally as "life-changing and irreversible". Everyone clutches their pearls over hormones and top surgery in a way that we don't for, say, letting children risk traumatic brain injuries playing football, or deciding whether to teach them another language, or raising them in church.

When I started testosterone at 21, I personally did not know for sure if hormones were going to "solve" anything for me-- I didn't know if testosterone would cure my dysphoria, let me "pass" as a man at least some of the time, if it would even effect me in the ways I was hoping for (or if it might change my body in ways that might distress me more than what I was already working with). I couldn't afford a gender therapist and didn't think one would help anyway, so I talked to trans friends instead (most of them my own age and, yes, on Tumblr) and the general advice was merely that transition is a trust fall; hormones only do what hormones can do, and "fixing you" is not on that list. But you can transition if you feel like it, and you can move at whatever speed you like, and if it sucks, you can stop! And I simply decided that, whatever came of it, I would more gladly cross that bridge of "regret" when I came to it than spend my life wondering about what could have been.

As it turns out, starting testosterone was one of the best things I have ever done for myself, one of the few big decisions I have been 100% certain I was correct on, even though I had no way of knowing that at the time. I obviously can't (and don't) promise that anyone who takes the same trust fall will be so lucky, but this way of discussing transition ahead of time-- as an expression of agency in itself, a validation of my right to make choices for my own future-- was highly effective for foreclosing on the very possibility of regret for me. This sort of framing is basically nonexistant in the cacophany of discussion about trans children because we already presume that children are incompetent to make their own decisions this way, and it loads all kinds of baggage onto adults to likewise justify why transition must be something other than what it is: a choice about one's future which is *always, necessarily* both reasoned and limited.

I think Jules Gill-Peterson (Histories of the Transgender Child) and Andrea Long Chu (My New Vagina Won't Make Me Happy) are the only people I have seen who openly advocate that the possibility of regret (or the failure to "cure" something) should not stop anyone from transitioning, even though it's maybe the most consistent attitude I have seen among the millennial generation of Tumblr Trans Kids that everyone loves to roll their eyes at. The use of children, autistic people, and people on the internet as euphemisms for people whose agency should be questioned and limited, and the inability to talk about transition in terms of bodily autonomy, are consistent problems in reporting-- it's why people are mad at the New York Times and the Atlantic, and why this piece kind of throws me off. I expected The One Percent to already be conscious of all this and not fall into hand-wringing about what young people decide to do with their own lives.

Methodical and useful statement on how we got here and how to unpick the stalemate. Clinicians, researchers and activists take note.