Travelling trans in the age of anti-intellectualism

I entered the US to attend a conference in Seattle. This post describes precautions for crossing the Canada-US border as a trans person (and as an academic researcher studying LGBTQ+ issues)

Two weeks ago I travelled from Toronto to Seattle to present research at the International Society for Autism Research (INSAR) conference. I was on a panel focused on the intersections between autism, gender-diversity, and gender identity development, and within the context of complex politics.

This was the third time I visited the US to present research on transition-related care since the surge in debates about it and the growing context of anti-LGBTQ+ politics in the US.

But it was my first time since Trump took office and introduced requirements that the passports of transgender travellers (and US citizens) bear the sex marker originally recorded on our birth certificates. This has affected not only trans Americans, but Canadians too. Canadian trans musician Bells Larsen cancelled his US tour due to this new legislation.

(Note: The passport policy impacting trans Americans was blocked in April 2025. It’s a little less clear to me about the current status for international travellers, but most of my Canadian trans friends/colleagues told me they will not take any chances trying to travel into the US for the time being.)

Today’s post is not about the conference itself, or the subject of the research presentation, but what it took to get there as a trans academic.

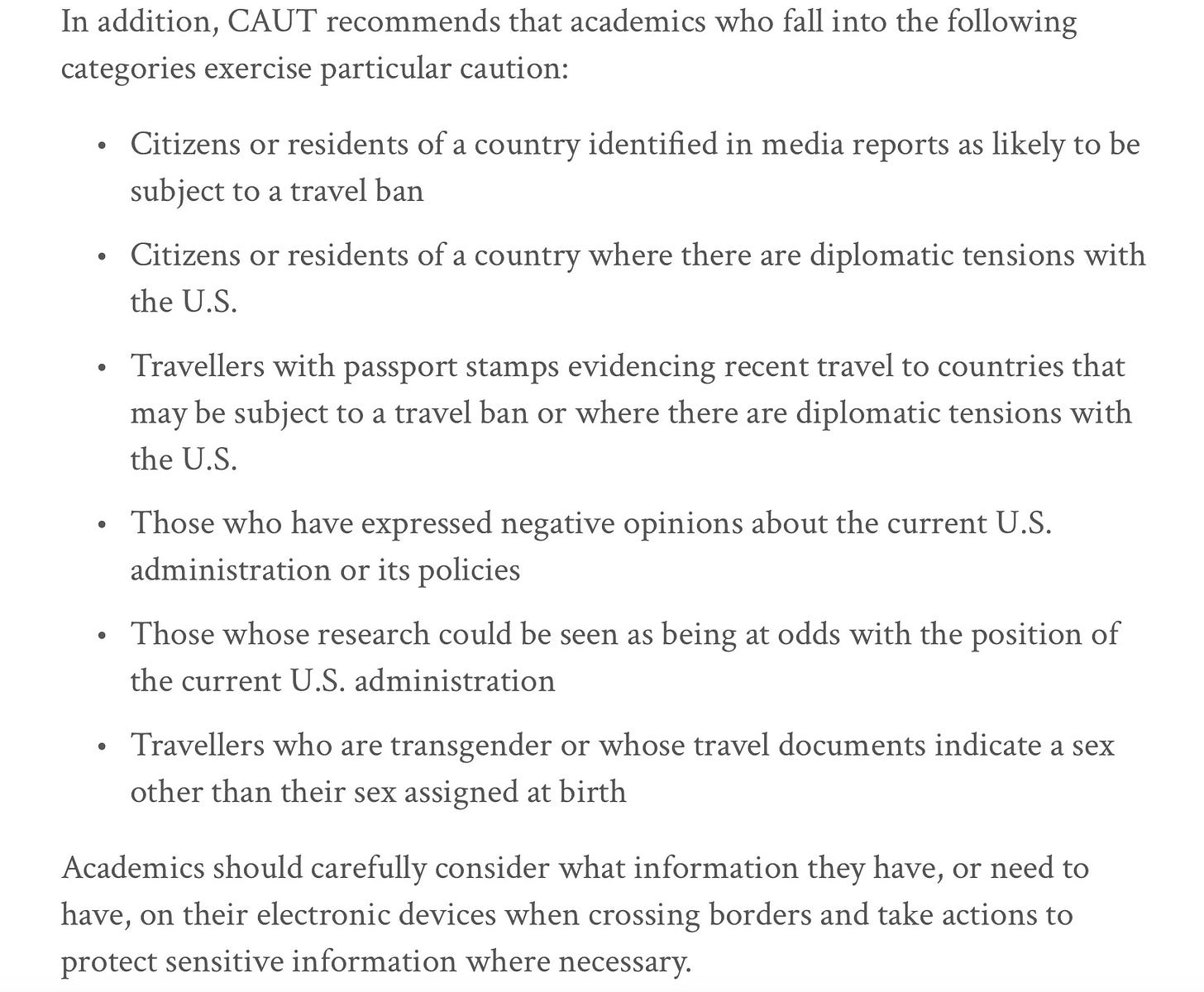

In the weeks leading up to INSAR, both my own university and the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) discouraged Canadian academics from going to the US, especially those “who are transgender or whose travel documents indicate a sex other than their sex assigned at birth.” This was the CAUT’s travel advisory:

I ticked off more than one of those boxes.

Also pertinent to this story, the National Institutes of Health cut LGBTQ+ research at its knees, gutting 125 million dollars of research funding. I know many US-based researchers who had key projects de-funded in this purge, studies that would have answered important questions pertaining to transition-related care.

I decided to attend the conference anyway, despite the warnings from CAUT, because I had made commitments to my American co-panelists. I also have my own principles and ethical values as an academic researcher to produce and share knowledge. These values feel even more relevant now as anti-intellectualism and threats to academic knowledge grow deeper roots day by day, amplified by MAGA, MAHA, and political polarization on both sides of the aisle.

To paint a picture: I am white and trans. The day before I set off on my trip, I turned 40 (!), but like many transmasculine folks, I am usually perceived as being late 20s or early 30s. I occupy an indeterminate transsexual/nonbinary/butch space where I typically pass as male. I was happy to change my body via testosterone and surgery, and when I started out my medical transition I thought of myself as a butch/genderqueer transsexual. Yet I have never claimed a male identity.

These identity labels have long helped me to make sense of my life, my desires, my behaviours, and my embodied feelings. But they don’t necessarily define me today any more than other personal descriptors that say something about my life trajectory (like being an urban transplant who grew up in rural Nova Scotia, or being an academic who has now spent half of my life in the “ivory tower”). Over time, as a person with my kind of history and as “trans” became more recognized in the public arena, identifying publicly with a trans man identity became easier, more socially intelligible. I suppose it fits, in many ways.

But these long-standing, fuzzy in-betweener feelings are also relevant to my passport’s sex/gender marker and my eventual willingness to travel to the US for the recent INSAR conference. Because, although I legally changed my name in 2011, I never changed my legal sex/gender marker. It never felt necessary.

This often sparks surprise, but I have been travelling with an “F” on my passport since I began transitioning 15+ years ago. So, for me, there was no need to change it back to enter the US as a transgender traveller. This is perhaps one of the more personal reasons behind why I felt less deterred from travelling to the US as a trans person, because having legal documentation that bears my birth sex is very normal for me—in airports and in life generally.

Crossing borders over the years has been largely uneventful. I am sure it is much to do with being a white Canadian and mostly male-passing. Having an “F” on my passport and other legal documentation hasn’t resulted in much more than a rare double-take. I get “sir” at the airport even after people review my documentation. I can’t say I’ve ever been discriminated against based on having an “F” on my I.D. There was a single time in Newark airport in 2013 when I was asked if I had ever legally changed my name (I have). Having to share my birth name, when I was very early in transition, felt uncomfortable and upsetting. But more often, even with an “F” on my passport, I have entered and exited numerous European countries, Latin American countries, and the US without issue.

Gratefully, travelling to and from Seattle across the US/Canada airport borders was also fine. I encountered no additional screenings or questioning. That was unlike the last time I travelled to the US in 2023, when I did get taken aside for additional security questions about the nature of my trip. This was after being forthcoming with border guards that I would be going to present at a “transgender health conference.”

Following travel advice issued by CAUT and my own university, and seeing other researchers being denied entry to the US, I took many more precautions than I ever have to travel to a conference, this time around:

I left my regular laptop at home to be safe. My university provided me with a blank laptop to travel to the US, which is a new service they started offering for academic travel to the US. Nice service, but also sadly speaks to the circumstances. This laptop had nothing on it: none of my research, no e-mail. Tabula rasa;

I e-mailed my presentation to myself. I normally print speaking notes before leaving for a conference, but instead I e-mailed notes to myself and printed the document once at the hotel;

I deleted all communication and social media apps from my phone, with the exception of texts (e.g., email, Reddit, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Substack, all gone for the duration of my trip);

In case I ran into any problems with border guards, I had an envelop of printed copies of my name change certificate and a letter from my doctor. The letter from my doctor explained the discrepancy between my passport gender marker and my masculine appearance caused by years of testosterone therapy under her medical supervision.

At Pride a few years ago, I ran into an old acquaintance who affectionately referred to us as “trans relics.” But I know people who I see much more as trans relics who transitioned in a very different era, in the ‘90s or ‘00s (“true trans relics”?). I thought about them when I travelled to the US carrying a letter from my doctor explaining that I was under her care.

In the earlier days of trans medicine, this was relatively common practice for trans people to carry around a letter explaining their gender transition, written and signed by one’s doctor. (Here’s one from the 1990s posted to Reddit). These “identity letters” were used in case of a need to prove one’s identity to any authorities.

Advised by the relics who came before me, I have had a copy of my name change certificate stuffed into the pocket of my suitcase since 2011.

All of the added stress and logistics aside, I was grateful for the opportunity to join this panel discussion in the US. Especially so because LGBTQ+ research at the intersection of autism that takes a neurodiversity-affirming and LGBTQ+ affirming lens is very much under threat in the US and elsewhere. It was a great conference, and we had many excellent and thoughtful questions in response to the panel!

Thanks for coming here and sharing your knowledge. American academics need international academics working with us more than ever, as you say. And the legal stuff is in a weird place in "blue states": despite all the passport policies you mention, my Massachusetts driver's licence now says "Sex: X", and I don't have any reason to expect that that will change.

Thanks for your efforts & sorry you had to worry about all that (blanking your computer & phone). Quite a sad situation here in the USA 😔