When real life defies the algorithm: My experience presenting on detransition at Naizen’s trans youth conference

I expected tension and conflict; instead, I found interest, understanding, and a shared path forward.

A few months ago, I received an email invitation from one of the co-founders of Naizen, a Spanish organization for families of trans children and adolescents in the Basque Country, where I live.

Naizen was hosting its first international conference about trans children and youth, featuring some of the leading experts in the field: Jon Arcelus (co-chair of WPATH’s SOC 8), Annelou de Vries (one of the pioneers of the Dutch protocol), and Joz Motmans (past president of EPATH), as well as individuals with lived trans experience, families, activists, and clinicians.

They wanted me to speak on a panel about changes of direction in transitions—that is, about detransition.

My initial reaction was fear. If you’ve been following the topic of detransition, then you’re probably aware that it is often mired in controversy and weaponized by various factions. Discussing this topic at a conference organized by and for families of trans youth—an audience that I imagined would be understandably protective and perhaps inherently skeptical of anyone even uttering the word “detransition”—kind of felt like walking into a potential minefield. The conference was filled with people deeply invested in gender-affirming care, including clinicians, activists, and others with personal stakes.

Despite my concerns, I accepted the invitation. It came directly from one of Naizen’s co-founders, a father of a trans child. He expressed a sincere interest in understanding the topic better, believing it was crucial for families and professionals alike. His curiosity and openness intrigued me, and I thought that perhaps this conference would be different.

At the conference, I was struck by the professionalism of the Naizen organizers, especially since it was their first time ever organizing a conference—which is surely not an easy task! Everything was perfectly planned, from the simultaneous translation between English and Spanish for attendees who didn’t speak both languages, to the clear program and scheduling.

The atmosphere also felt like one of genuine inquiry. One of the organizers made this clear during the opening keynote, where he said that, although we probably came from different backgrounds and had different ideas, we were all in the same boat when it came to caring for and supporting trans youth.

But perhaps what impressed me most was their deliberate curation of panels. They weren’t afraid of differing viewpoints; in fact, they actively sought them out. One panel featured a sexologist with 30 years of experience working with trans patients and a queer theorist with many years of political activism discussing trans identities. Their contrasting perspectives made for an enriching discussion and proved Naizen’s commitment to fostering dialogue over dogmatic agreement.

Of course, there was some tension between speakers—and speakers and attendees—at times, but this didn’t obscure the conference’s ethos: expanding understanding, not creating an echo chamber.

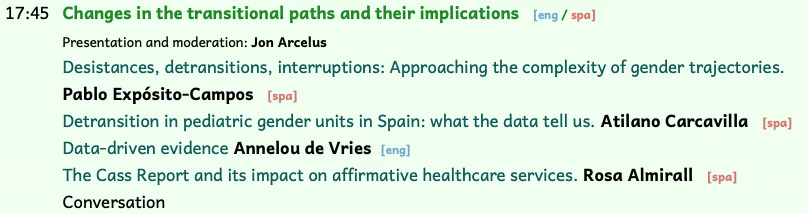

My panel was called “Changes in the transitional paths and their implications.” I was tasked with speaking about terminology and concepts, such as what detransition is and how it differs from other phenomena like regret. I also discussed what the research says about the psychosocial experiences of detransitioning individuals and how we can support them. Sitting alongside me were Annelou de Vries, a child and adolescent psychiatrist whose work I deeply respect; Atilano Carcavilla, a pediatric endocrinologist from a gender clinic; and Rosa Almirall, a gynecologist and the founder of Trànsit, a renowned gender-affirmative service that has cared for thousands of trans people over the years in Catalonia.

Given how detransition is discussed in public discourse and the surrounding culture wars, I prepared myself for potential tension or even disruption, experiences that I know have occurred elsewhere when similar controversial topics have been addressed.

I presented the available research and empirical data on detransition, acknowledging the profound complexity of the topic upfront. I emphasized that there are no easy answers or one-size-fits-all narratives and that our primary collective responsibility is to support individuals wherever their path takes them. I made it clear that our goal is to understand the full spectrum of gender-related experiences, including those who change direction and detransition.

As I spoke, I scanned the faces of the attendees. I saw not hostility or skepticism but attentiveness. People were listening—truly listening. There were nods and note-taking, and the atmosphere was one of genuine engagement. When the panel concluded, there were no criticisms, accusations, or grandstanding—a contrast to the tensions I’d observed on other panels before mine.

Many people approached me after the panel, including clinicians interested in learning more, parents of trans children who expressed gratitude for the nuanced discussion, and the conference organizers, who reaffirmed their interest in continued collaboration on this topic. A few individuals who had previously expressed skepticism, even opposition, to my work and the idea of discussing detransition on a panel came up to say they genuinely appreciated the presentation and found it insightful. I had many good conversations after that.

This experience was transformative in a way. It was the antithesis of what I had imagined, leading me to deeply reflect on the contrast between the often toxic, polarized discourse on social media and engaging with people face-to-face.

The motto of the Naizen conference was “comprender para poder acompañar”—“underpinning support with knowledge.” This ethos permeated the entire event, but it felt particularly resonant during and after our panel.

I didn’t see a room full of “ideologues”; I saw loving parents, engaged clinicians, and individuals willing to grapple with complex realities. They weren’t looking to shut down conversation. They were looking for information and understanding because they believed that detransition is a possible experience, even if it’s not the majority experience. It could happen to their children, patients, or people in their communities. Genuine care demands understanding so that we can provide care and support.

My presentation was nothing out of the ordinary. It was just an attempt to share knowledge, to recognize uncertainty where it exists, and to center the human beings at the heart of these difficult experiences. But perhaps this framing—one that prioritizes compassion, acknowledges complexity, and focuses on support rather than “scoring points”—was crucial. It allowed people to engage with curiosity rather than defensiveness.

I think what Naizen achieved was remarkable. They created a space where the sensitive topic of detransition could be discussed constructively and respectfully with a focus on learning and understanding. This made me wonder if the intense polarization we often see is a media-amplified, algorithm-fueled distortion of where most people actually are.

This experience suggests to me that, when we step away from our keyboards and meet in good faith, we have an enormous capacity for understanding and empathy. We also have a shared desire to support young people, no matter where their gender transitions take them.

It also reaffirmed my belief that the “middle ground”—a space of nuance and sensitivity to all experiences with a focus on support rather than ideological warfare—is not only possible, but also essential.

Frankly, it gives me hope. And this is a path I’m determined to keep walking.

Thank you for reading The One Percent!

If you enjoyed this post, please share it with your friends, family, or colleagues:

You can also subscribe for free to receive new posts and support our work:

Without experiencing puberty how do you know who us "trans children"? Puberty is NATURAL TRANSITION, duh!